INCLUDED IN THIS PACKAGE:

There’s a German Word for Everything (+ The Inaugral Voice Note Version)1

Media Review

Anisa’s Writing Corner

Conclusion

Skip to any section you would like <3

There’s a German Word for Everything

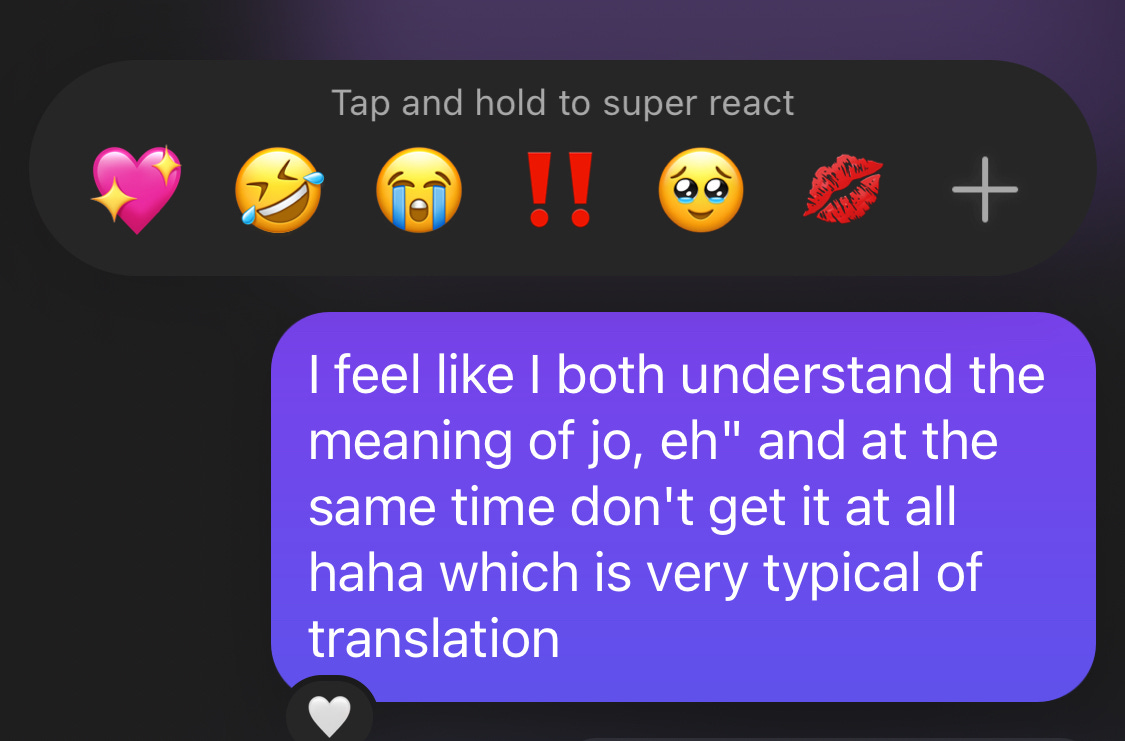

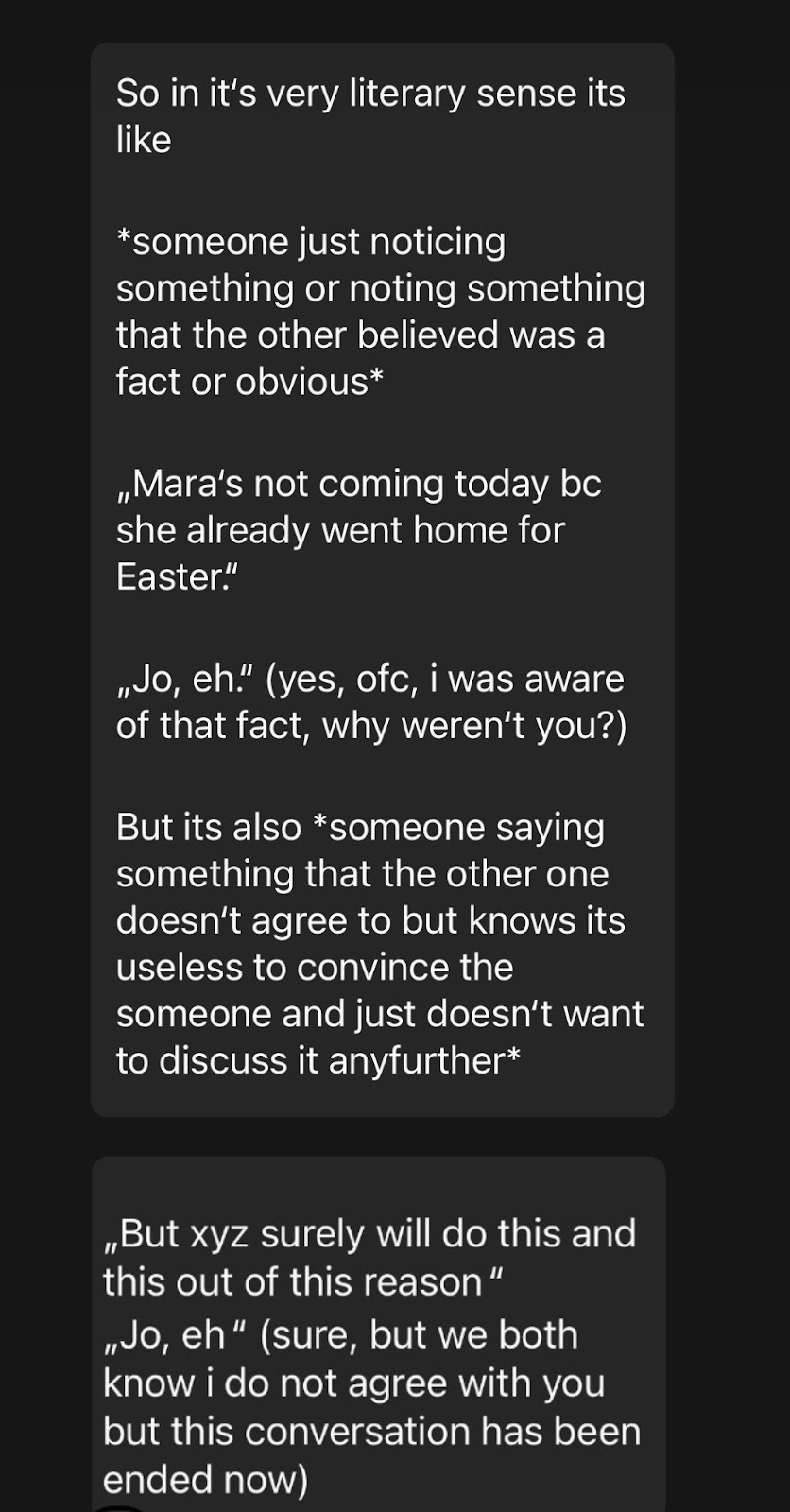

The other day, my dear friend Alina went through the particularly grueling task of explaining what “Jo, eh” means to a non-Austrian. (that would be me. Hello.) While the conversation we had was illuminating, it did make me think about the topic of translation.

I will be frank—for much of my early life, I didn’t understand translation. I set up a false equivalency between, for example, the English versions of “The Count of Monte Cristo” and the original French. I don’t even remember the name of the translation that I read. I bought my Russian lit from Penguin because I preferred the covers to the Oxfords. The first Iliad translation I bought insisted on calling Zeus Jove. I skipped introductions and didn’t read translation notes. I wouldn’t say I didn’t care, because that necessitates some kind of cognition. In reality, I just didn’t know, until I accidentally became a classicist and had to learn.

Earlier in the year, I was privileged enough to meet Anton Hur and hear him speak about translation. (Perhaps you’re familiar with his work— he translated “I Want To Die But I Want To Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Se-hee and my signed copy of “Cursed Bunny” by Bora Chung proudly bears his signature). He described having trouble nailing a particular author’s voice in English. At the time, he wound up asking the author what they wanted their English voice to sound like. He asked what they liked to read in English, and the author mentioned this specific English-language author, and it clicked for Anton that that is what it felt like to read [Insert name of author’s work] in Korean. Eventually, he was able to translate the work while using that English-language author as a sort of template. A translation guide, if you will.

While there are moth holes in the memory, hence the lack of names, I do remember something important I learned from this. Translation is more than making x in one language equal to y in another. It is a reshaping and reconstructing of a voice, and part of a writer’s voice is rooted in the language that they speak.

Spoken language has all these slight fluctuations, changes in pitch and tone and politeness. We tend to leave those to the domain of spoken language, and ascribe semantic fluctuations to written translation, but I think that sets up a false dichotomy. Translation does not just reconstruct semantic meaning—it conveys tone and pitch, intention and inflection. In actuality, a translator is very much like an author.

It’s the Ship of Theseus debate all over again. When we read a novel in translation, are we reading that novel, or a new one? If all the words are reconstructed, piece by piece, can they still be called the same? Does calling the Achaeans “Greeks,” as Emily Wilson does in her translation of the Iliad, change something fundamental about how we read the work? Does translating “saudade” as “longing” miss the mark?

Currently, I’m reading a great deal of novels in translation. Emily Wilson’s Iliad, Fagles’s Oresteia, McDuff’s Crime and Punishment, Hersey’s Vita Nostra. It is perhaps odd to attribute them to their translators, but we will likely never know where the translator ends and where the author begins. That’s inevitable.

Like “jo, eh,” there will always be things that a particular culture found important enough to give voice to. Thus, there will always be things that are untranslatable, because they describe a culture as much as they do a phenomenon. So the word saudade in Portuguese doesn’t mean “longing for/missing someone or something that’s no longer there”, it is the Portuguese and Brazilian way of longing for or missing a not-there thing. It has the history of the Age of Exploration behind it, of explorers and family parted by the seas, but it can equally be an undirected longing for something beyond the here and now.2 It is injected into literature, threaded through the being, and it exists as a word because the Portuguese thought it pervasive enough to name. It is melancholic and contemplative, not acutely dismal, a soft pang of longing, a wistfulness. It is homesickness, person-sickness, somewhere-other-than-here sickness. Lispector says saudade is a “bit like hunger,” only sated by the presence or even absorption of the person being missed.

I like the way Aubrey F.G. Bell puts it.

“The famous saudade of the Portuguese is a vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist, for something other than the present, a turning towards the past or towards the future; not an active discontent or poignant sadness but an indolent dreaming wistfulness.” – Aubrey F. G. Bell, In Portugal, 1912

Sum it up in a word in any other language. You can’t. Even the Welsh hiraeth, which is often defined in similar terms, is so unique to the Welsh longing for a Wales pre English colonization that it cannot possibly be applied to the very Portuguese saudade. How do you translate a word like that? You don’t. You can’t. Some words take a sentence to explain.

Words like these are the link between language and culture. They tell us what a people find important. So the Greeks had eight words for love, and modern Arabic has seven—my friend Maya told me that the highest one is عشق, loving someone to the point where you feel pain in their absence, although that’s an oversimplification.3 The Germans, I like to joke, have a word for everything. The popular example is schadenfreude, but Alina told me about the word weltschmerz—the pain you feel for the state of the world, and the helpless inability of being too tiny to fix it.

These words are the reason Dostoevsky and Gogol feel Russian, the reason Hugo and Dumas feel French. There is a kind of constant feedback loop between the cultural milieu and the language created to describe things within it. It also accounts for continuity—so Vita Nostra feels representative of Russo-Ukrainian literary traditions, and Murakami may remind us of Dazai. We may not be able to understand everything about why these traditions exist, but we borrow bits from here and there and breathe new life into old concepts. So, when we see Walt Whitman’s “I sing the body electric,” we remember Virgil’s “I sing of arms and the man.”

It is also, I think, the reason that good translation scratches an itch. It’s the reason Kafka fell in love with Milena, who translated his works and saw him in the process. I haven’t finished “S” by Dorst and Abrams just yet, but this process of translation plays a huge part in there too. To cross the lacuna is an impossible pole-jump, so we applaud when someone does a good job of it. It’s why I personally adore Emily Wilson.

Full disclosure though: I haven’t finished R.F. Kuang’s Babel, but I had a feeling that I was missing out on some genius, inventive quote that would tie this newsletter up in a bow. And then I found it, so I think I’ll end with it.

How can we conclude except by acknowledging that an act of translation is always an act of betrayal?” - Babel, by RF Kuang.

Media Review

BOOKS:

March was a good reading month, in terms of reading actual books. I found a new favorite, continued the Truly Devious series with The Vanishing Stair, and read outside of my normal genre with Bye, Baby (which was interesting, although it left me with mixed feelings).

A Study in Drowning by Ava Reid is undoubtedly my favorite read of the month and possibly one of my favorites reads of the past five years. If you like dark academia, this is that aesthetic with a twist. It’s got some lovely commentary, faux scholarly articles, and a well done Gothic house (incidentally called Hiraeth: I heard the author talk about the meaning of the word two nights ago).

MUSIC:

It’s been a Eurovision month for me. My brother and I have been going through all the songs, and there are so many good ones this year. I’ve found myself writing to Luktelk and The Tower and bopping to La Noia, Zari, Jako, Fighter and of course, Europapa (I wouldn’t be surprised if it winds up winning). The Code is also an insanely good song; it shouldn’t work, but it does. It’s hard to list all my favorites, but I do have a playlist, if you’re interested.

Otherwise, I’ve become a stereotype and had a solid month of listening to very little outside The Smiths, The Arctic Monkeys, Queen and The La’s. Lots of The’s. Some favorites include This Charming Man, The Arctic Monkey’s entire discography, and There She Goes. Also, shoutout to Too Sweet, Stuck on The Puzzle, and Venus for getting me through my academic essays and Camp NaNo.

THEATER:

In other news, seeing Phantom of the Opera was one of the highlights of my year. Our Phantom was an amazing singer, the set was incredible, and the acting and music were soul-stirring. When the music first started playing I almost cried. Phantom, unlike Hamilton or Macbeth, isn’t one of those plays that I allowed myself to get deeply entrenched in before seeing it. However, I think I’m obsessed.

Anisa’s Writing Corner

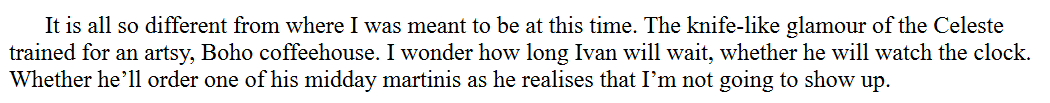

It feels so good to be writing again. I’m blurring March and April together now, but that’s because my writing progress feels very continuous. Since March, I’ve been revising Astericus. Since April, I’ve been working on Project V.

Something very terrifying happens when I’m drafting for any NaNo event during the year. Everything I write goes into a memory wasteland, unless I have an outline, which I currently don’t. That means I’m questing to finish the last 30% of a draft that had previously been plotted step by step. I don’t remember what I wrote yesterday, and I don’t know what I’ll write tomorrow, but I think it’s all turning out well. These last few chapters have come alive all on their own, and I’m in that ski-slope, last-act stage that’s always the most fun. I hope I’ll have more to share with you soon.

CONCLUSION

By now, I’m sure some of you are familiar with my never-really-conclusive conclusions. Can I pretend you don’t mind? March was a bit mad but it was lovely. I hope you had as much fun as I did last month, and I hope we all have an amazing April.

Mach’s gut,

Anisa

A new segment! From now on, expect to see the rambly, essay-esque part of my newsletter read out loud :) If I messed up any pronunciations here, I’d tell you that I’m not a prescriptivist and so you shouldn’t hold me accountable. The first half is true, the second is false (please feel free to correct me <3).

See more about Saudade here: https://www.portugalist.com/what-is-saudade/

She also told me that each letter in Arabic has a numerical power ascribed to it, that usually corresponds to the power of the word’s meaning. ع and ق are hard to pronounce (don’t I know it), so they have high numerical power, which is part of what makes عشق so powerful semantically. I’ve tried to pronounce it the Levantine way.