INCLUDED IN THIS PACKAGE:

Cultivated Identity and The New Aesthetic Age

Media Review

Anisa’s Writing Corner

Conclusion

Skip to any section you would like <3

Cultivated Identity and The New Aesthetic Age

Imagine being an eavesdropper for a second. Unseemly I know, but forget about the scandal and just listen.

There are two girls, at a cafe, somewhere between late teens and early twenties. Young and pretty, laughter high and bright like sunlight striking water.

And you can’t quite hear what they’re saying—it fades in and out—but if you strain your ears you can listen. One of them speaks confidently: “Kafka was a teenage girl.”

The other nods and says: “he understood me.”

She shows the other a picture of a knife tied up in a bow, and for some inexplicable reason it makes them laugh. And then they go on about Clarice Lispector and the coquette aesthetic, stuck somewhere between the well-read girl and the returnee Tumblr nymphet.

Some of you may be able to hear them, and some of you are part of them, and some of you might not be able to visualise this conversation, in all its theatrical absurdity.

But they represent identity: something that has always existed. Today we just discover it differently; we don’t happen on it anymore. These girls excavated who they were, instead of just simply finding out. They chose. And problematic conventions of their particular aesthetic aside, I don’t mean to judge them. When we unravel any kind of aesthetic, we find darkness. Dark Academic obsession and eurocentrism, the stereotypical infantilization of the hyper-feminine coquette. No aesthetic is exempt from criticism—except maybe cottagecore? Whatever—point is, anything in excess can become an epidemic, but not everything that spreads is a scourge.

So, I’m not trying to drag an aesthetic young women currently adore1. Instead, I’m trying to say that that we have all become curators.

You have your aesthetic. I can’t describe it for you, but something came to mind as you read that. Maybe you find solace in the sun, moon and stars, or maybe you are minimalist and modern. Maybe you are gilded and elaborate and baroque, or maybe you are boldly brutalist. Maybe you look at a neoclassical work revitalised by neon pink letters, and feel seen and adored by Ottessa Moshfegh. Whatever you choose, you seek out things that fit with the portfolio of your person. That wallpaper. That book. That song. Everything has to align perfectly, aesthetically, so you can see a lookbook and laugh because it’s you.

And maybe it is. Either way, I wouldn’t begrudge you your poison. I started with the Secret History and dark academia moodboards, and ended up learning Latin and reading about post-structuralist feminist theory. Like my text from earlier indicates, I’m no stranger to feeling like a stereotype.

I’m interested in the why of it. What is it about the age we live in that makes us self-define? We’ve always wanted to be something. It is human, I’m sure, but never has it ever mattered this much. Being a Dostoevsky girl or a Murakami boy or someone that watched Fight Club and got it has never been so crucial, so defining. We do it in a thousand, microcosmal ways, but all of us love to manipulate perception.

And some of you will already know why. When I talk about the mortifying ______ __ _____ _____, you will already fill in “ordeal of being known”, because you get it. You’ve seen the Tim Kreider quote and you get it. We have to be seen to be known and to be loved, but being seen wrong mucks it all up. And that’s scary.

Pause. There are two kinds of quotes. Only two. One you understand, and one that understands you. The first makes you feel smart at the imaginary dinner parties you mentally entertain yourself with. The first gives you something to say. The second makes a piano of your lungs.

Can you imagine, for a minute, a quote ripping out your lungs? You are wild and you are windless but the piano starts to play. It plays a tune you know, music only you can hear. An opera with no other audience. A concert with no crowd.

Allegro. I can see you. Andante. I am here.

It is more than just a quote; it is a mirror.

What is a quote that understands you?

I’ll go first.

Clarice Lispector (and I’m aware of the irony of quoting her) once wrote “I only achieve simplicity with enormous effort.” That is a quote that understands me. Is that innocuous? Good, because I’m not done. Back to our friend Tim Kreider.

He writes (and does so brilliantly) this in his essay “I Know What You Think of Me”:

“Hearing other people’s uncensored opinions of you is an unpleasant reminder that you’re just another person in the world, and everyone else does not always view you in the forgiving light that you hope they do, making all allowances, always on your side. There’s something existentially alarming about finding out how little room we occupy, and how little allegiance we command, in other people’s heads.”

And also this:

“It is simply not pleasant to be objectively observed — it’s like seeing a candid photo of yourself online, not smiling or posing, but simply looking the way you apparently always do, oblivious and mush-faced with your mouth open. It’s proof that we are visible to others, that we are seen, in all our naked silliness and stupidity.”

Do you get it now? Why we do this? Why we care enough to cultivate, curate, cast the spell?

To manipulate perception is to take power over the mortifying ordeal: the thing we fear that drives us to control. To succumb to an aesthetic is to be sovereign. We dictate how we are seen, how we are feared, how we are loved. To wield an image is to wield a weapon.

And it’s nice. It’s nice to be known for something. It’s nice to have an image that lacks uncontrollable variables. Social media makes it easy to stay in character, and it’s so lovely to appear so put-together.

I learn Latin because I love it, and quote Cixous because she’s a mind. But it can be nice to know that people see the pipeline. They don’t see my Notes App Poetry, or the thoughts inside my head, or anything else that could potentially be embarrassing. But they see enough of me to make a judgement, and an aesthetic is a means of regulating just what they can judge.

Can you really blame a human for being performative? When we make art, when we write stories, when we spin wonders at the theater? To shame a human for being theatrical is to shame a fish for being able to swim. It’s innate—not immune to criticism—but still vital. Fundamental. We are social creatures, and the world is a stage. Who can blame us for play-acting?

And I should emphasise this—most of our aesthetics do define us. Incompletely, to be sure, but a definition is still a definition. It’s not bad to have a brand, and we do choose. Usually, we like what we like, and then make a spectacle of it. It’s less like prevarication and more like embellishment. It’s making fancy clothes out of pre-existing fabric.

Still though: it’s nice when something else slips through the cracks. Something candid, less controlled, but just as true.

Someone asked me recently if I was a writer, and when I told him ‘yes’, he said he knew. And I thought, isn’t that so very cool? So rarely am I looked at and perceived just as I am. But in that moment, I was sixteen and where I wanted—still want—to be. My image leaked past its pre-established borders, but fair enough. It was nice this time.

But aesthetics are still alluring. They give us colour, depth and range. A future and a present and a past.

Nevermind the deeper end. Focus on the feed. Pretend I am pristine and make me smile.

“Beauty is a form of Genius--is higher, indeed, than Genius, as it needs no explanation. It is one of the great facts of the world, like sunlight, or springtime, or the reflection in the dark waters of that silver shell we call the moon. It cannot be questioned. It has divine right of sovereignty. It makes princes of those who have it.”

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

It’s interesting to me, because our new aesthetic age is similar to the first one (back in the 19th century) but also paradoxically opposed. Back then, l’art pour l’art, or art for the sake of it, was a response to the harsh materialism of the industrial age. It was less about beautiful things portraying meaning and more about them not having to. Now, we place value on aesthetics precisely because of their imagined meaning. Being coquette makes you pretty and feminine. Being darkly academic makes you smart and intriguing. Being into cottagecore makes you a fairytale creature. L’art pour l’histoire, art for the story.

I think we all want to be understood, but that’s riskier than wanting to be clever, or enviable, or interesting. It’s more attainable to desire wittiness or humour or something on the surface that doesn’t rely on being soul-naked in front of others. We crave that sweet-spot between being known and being unfathomable. We want to be worth looking at, or say things that are worth quoting. We want and want and do not always get.

But can I be honest? I know all this, and still I want. I want to be magic.

I want to be a library. I want to be deep enough to drown in. I’m scared of someone diving only to hit those square blue tiles.

Ocean sand is better; water’s wetter, somehow, when you can’t see the bottom of the pool.

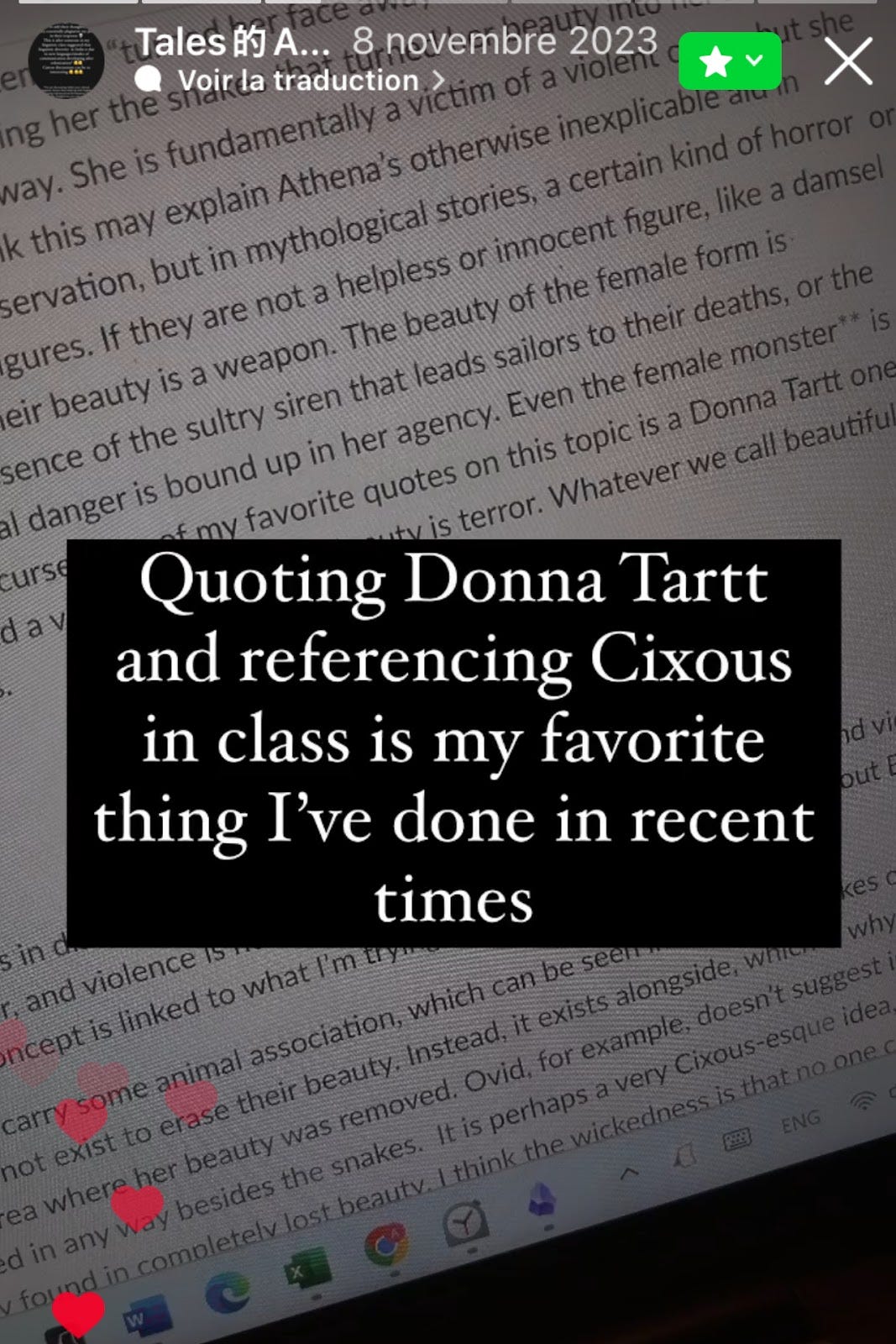

“Does such a thing as 'the fatal flaw,' that showy dark crack running down the middle of a life, exist outside literature? I used to think it didn't. Now I think it does. And I think that mine is this: a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs.”

Donna Tartt, The Secret History

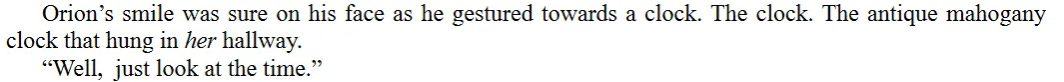

Ending this segment with Donna feels fitting. I read The Secret History and it stuck with me for many reasons, but it always makes me think about the implications of hedonistic aestheticism. Of manipulating perception, of enjoying being seen in a certain light. Of romanticizing an unrealistic image. I always joke that I got the point, but I still daydream about studying classics in a small liberal arts college in Vermont. It’s ironic that a book that critiques our relationship with aesthetics has served to make its own aesthetic popular. But there’s just something so endless about an aesthetic, about the ways we choose how we’re seen. About the tinny truth of it, about the things we fake. Perception is intriguing, excruciating, exciting. Our relationship with it is complex. As many other things have, it has bled into my writing, so I’ll end by sharing this snippet:

And there she is, getting up from the chair with a smile on her face that Katya just put there—and suddenly I’m a half ashamed teenager again, drawing back so she doesn’t perceive me and lose the smile that has just lit up her face. She hasn’t seen me yet, and I am struck by the crazy idea that maybe I should stay where I am, so she will not see me at all; because surely if she sees me she will see my naked self? Surely she will know I’m just a girl?

Project V, Chapter 14

MEDIA IN REVIEW

SHORT STORIES:

February was an extremely busy month, academically, so I found myself going on a bit of a short story bender in the first half of the month. Amazon has these collections that I’ve been tearing through, and I’ve liked a lot of the stories I’ve read. Here are my top three out of the eight I read last month:

The Six Deaths of The Saint by Alix E. Harrow—This is undoubtedly the best short story I’ve ever read, which is apparently something I mentioned in my one sentence good review. It’s literally so perfect, so stirring, so self-contained and cyclical. (And it might make you cry).

Best of Luck by Jason Mott—Fair warning, this one gets a little bizarre, but it’s so brilliant. It reminded me a lot of Vicious by V.E. Schwab. If you’ve been around for a while, you might remember that Vicious is my favorite book, so I don’t make the comparison lightly. There’s just something about best friends turned enemies that does it for me.

The Best Girls by Min Jin Lee—I really don’t want to spoil this for you, so I’m not going to describe my reaction to it. My advice: read it without knowing anything but the blurb.

Side note—all of these are on Kindle Unlimited!

BOOKS:

February saw me read a lot of things I didn’t like, but two books did stand out.

Everything Sad is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri—if you read any book from this list, please read this one. It’s the best middle-grade I’ve read in recent times.

If You Could See The Sun by Ann Liang—I’ve been wanting to read this forever—a friend of mine loves it—but then I saw that it was on KU and finally caved. It was so refreshing and so much fun! If you’re in a reading slump, pick this up.

ANISA’S WRITING CORNER

Not a lot got done in February, writing-wise. I wrote two poems I’m super proud of, worked out the prologue for a project I’m excited about, shared ISSTF on Instagram, and started a new project that is making me feel like a fish out of water. Besides all that and besides editing Astericus, there’s really nothing new. However, there is one big announcement I will make in 3…2…1…

My cover reveal will be posted on my Instagram in exactly 17 days! Stay tuned! I can’t wait for you all to see it. My friend Alina did an amazing job with it and it’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

CONCLUSION

February was a fun month. I forgot it was a leap year, and ended up being so happy when I woke up on the 29th. This conclusion is a bit like that left-over bit of February. Not much is added, but something changed. I still left out a huge part of the month so expect that in next month’s newsletter, but for now, I will settle for ending with a see you around.

I hope February was amazing for you, and either way, I hope March is better.

With love,

Anisa

Don’t be surprised if I do later on <3 I’m saving my aesthetic critiques for a different format…

Beautifully written, I’ve been thinking about cultivated identity for a while and “L'art pour l'histoire, art for the story” is such a great way of putting it.